-

Kaleidoscopic Korea 2: Hangeul Exhibition

Post Date : Apr 10, 2024

Event Date : Apr 26, 2024 - Jun 30, 2024The Korean Cultural Centre presents <Kaleidoscopic Korea 2: Hangeul Exhibition> at the KCC Gallery from April 26 to June 28. Kaleidoscopic Korea 2: Hangeul Exhibition - 2024. 4. 26. - 6. 28 - The KCC Gallery (101-150 Elgin St., Ottawa) Kaleidoscopic Korea 2: Hangeul Exhibition Opening Reception - 2024. 4. 26. Friday, 5 - 7 pm. - The KCC Gallery (101-150 Elgin St., Ottawa) - Registration link to participate: https://forms.gle/PFgNwNXLL9qBstj79 - Inquiry: The Korean Cultural Centre (canada@korea.kr/ 613-233-8008) From February to June this year, the Korea Cultural Centre Canada is organizing Kaleidoscopic Korea, a series of exhibitions showcasing Korea's timeless beauty. Borrowing from the theme of a kaleidoscope, which constantly intertwines underlying elements and intermediaries to create dynamic imagery, this exhibition series presents various facets of Korean aesthetics—from lifestyle to the Hangul writing system; from tradition to the present; from Korea to Canada. The objects displayed in the exhibition have been produced by prominent Korean cultural institutions such as the National Folk Museum, the National Intangible Heritage Center, the National Hangeul Museum, and the Korea Craft & Design Foundation. In addition, the exhibition features contemporary Canadian craftworks inspired by traditional Korean arts. These diverse subjects and identities envision a completely different dynamic of Korean beauty for the future, encouraging dialogues between different objects and concepts through communication, interconnection, and convergence. <Kaleidoscopic Korea 2: Hangeul Exhibition> is organized around two main themes: The first theme is Hangeul cultural products. Hanguel means the Korean alphabet. This special exhibition of Hangeul Cultural Products is sponsored by the Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the National Hangeul Museum, and hosted by the Korea Cultural Center Canada and the Korea Education Culture Foundation. The Hangeul cultural products on display were developed through a competitive selection process of the “Promotion and Support Project for Hangeul Industrialization”, which was initiated by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the National Hangeul Museum. The Program aims to develop and promote the value of Hangeul culture while responding to the growing global interest in Hangeul and Hangeul culture. The exhibition showcases a collection of more than 30 unique Hangeul design cultural products. These include practical goods, Hangeul board games, Hangeul block toys, animations, and Hangeul fashion works. Each item is a testament to the aesthetic beauty of Hangeul, blending it seamlessly with practical functionality. The second theme of the Hangeul exhibition is "Hangeul as a contemporary art medium." Jongwook Park, a Montreal-based Korean Canadian artist, utilizes Hangeul to visualize his emotional and psychological negotiation to express himself as an immigrant between his mother tongue and newly adopted languages. By approaching pen and ink drawing as fundamental tools of his practice, Park attempts to discover the unique treatment of line drawing in his works in flat, dimensional, and moving formats. Artist Statement: Borrowing the concept of fantasy (from Korean folk paintings) and heroism (from graphic novels), I utilize the visual and conceptual elements of these two iconographies to convey the unsettling feelings and fears of being unfamiliar to others. As my hand drawings with Korean alphabets slip into other contexts or other mediums, I would like to share my experiences of connection and disconnection that I have been developing. I use visual symbolism and intuitively generated drawing compositions. Using the Korean alphabet as a symbol to restore communication, I would like to share an endless narration and expand a core theme - alluding to inner struggles. The compositions of the work I develop are like phrases or lines of a poem constructed from images from my subconscious, excavated through the meditative process of doodling. Through these symbolic forms of the Korean alphabet, I want to create a surreal landscape to evade negative feelings and my frustration that comes from conditions of emotional displacement. I aim to generate dialogue between the forms while maintaining the narrative possibilities that originate from my hand drawings, conveying this transformation of language that is received and brought through a process into meaning and comprehension. Park holds an MFA in Communication Design from Sangmyung University (Seoul) and a diploma in Animation from LaSalle College (Montreal). His work has been presented in exhibitions and publications in Canada, the United States, Finland, South Korea, and Japan. <Jongwook Park - Artist Talk> - Friday, June 7, 6-8 pm - The KCC Canada (101-150 Elgin St., Ottawa) - Registration: https://forms.gle/qyFA4RDjYYqMpZe49 - Inquiry: canada@korea.kr / 613-233-8008 -

K-Lifestyle: Fiber Artist Chung-Im Kim

Post Date : Mar 11, 2024

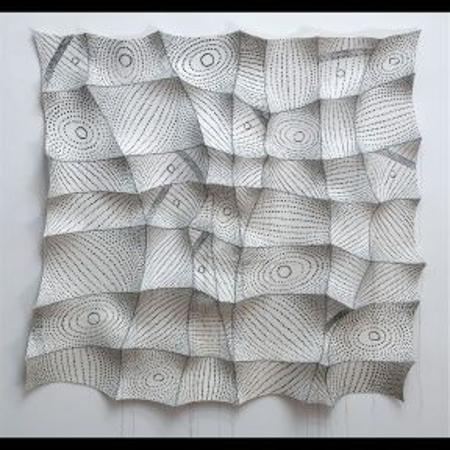

Event Date : Mar 15, 2024 - Mar 17, 2024The Korean Cultural Centre Canada hosts an artist talk by Chung-Im Kim at the KCC on Friday, March 15, at 5:30pm. Chung-Im Kim is one of the participating artists in the Kaleidoscopic Korea: K-Lifestyle exhibition, which is on view at the KCC Gallery until April 5. Registration for Chung-Im Kim Artist Talk: https://forms.gle/pLZ3yprd8UXCsLUM8 About the Artist Chung-Im Kim has received accolades and exhibitions for her work in many prestigious institutions such as the Boston Museum of Art, the invitational Bojagi Exhibition at the Suwon Park Museum in Korea, the Museum Nagele in the Netherlands, the Wollongong Art Gallery in Australia, the Belgian Triennial Contemporary Textile Arts Exposition and the recent traveling exhibitions at the Poikilo Museum in Finland, Tamat Museum in Belgium, Dronninglund Kunstcenter in Denmark, and the Textilmuseum in Germany. Kim's design and execution have been honoured with prizes and awards in many international art competitions. She received her MFA from Seoul Women's University in 1984 and immigrated to Canada in 1990. Since then, Kim had worked as freelance designer for many years and also taught at OCAD University in Toronto since 1997 until her retirement in 2021. She is represented by the Oeno Gallery. https://chungimkim.com/ Artist Statement “fingerprints of the earth #1” and “fingerprints of the earth #2” 2021 "This set of two artwork was inspired by the formation of embedded marks permanently visible in the immense boulders of Big Bend National Park in Texas. I wanted to explore the quiet but roaring scale of time and space in that environment. Geometry has always been deeply imbedded in my practice. Being captivated by natural wonder, my enduring interest in geometries and mathematical structures was in some way revived/heightened by analyzing the found objects in natural world. They exemplify the fundamental rules of pattern making in design and reveal the structural secrets through their architecture. This essential understanding stimulates my imagination towards building a complex undulating surface with both regular and irregular modules. The role of mathematical thinking in my work is as inevitable as that of nature itself. Ideally, I would like to portray a coherent philosophy rooted in both nature and science, yet I would contrarily also like to shake up their logic in the hope that my work might transcend my current knowledge. Or perhaps be allowed to become more spontaneous and less predictable." Chung-Im Kim, fingerprints of the earth #1 & #2, 2021 “dawn” 2009 "The modules in many different scales and shapes in my work represent certain growths or changes brought about through passages of time. I imagine them symbolizing the fragments of memories that we experience through our conscious/unconscious journeys. Through them I want to explore the chaotic order resulting from many small pieces containing image fragments. I would like to see each of the parts as an independent soul presenting unique power and energy that then together become an entity as cells to a body. In addition, the aesthetics of Korean bojagi has genuinely ingrained in my work even though they don’t necessarily appear so. Especially the random swatches of the humble bojagi cloth were a big inspiration to craft the structure of my work as modules. I hope to capture the unpretentious spirit from the traditional Korean bojagi and evoke a new birthing tension when all are gathered in my felt work." Chung-Im Kim, dawn, 2009 Further information on the Kaleidoscopic Korea II: K-Lifestyle exhibition is available here. -

From February to June this year, the Korea Cultural Centre Canada is organizing Kaleidoscopic Korea, a series of exhibitions showcasing Korea's timeless beauty. Borrowing from the theme of a kaleidoscope, which constantly intertwines underlying elements and intermediaries to create dynamic imagery, this exhibition series presents various facets of Korean aesthetics—from lifestyle to the Hangul writing system and K-food; from tradition to the present; from Korea to Canada. The objects displayed in the exhibition have been produced by prominent Korean cultural institutions such as the National Folk Museum, the National Intangible Heritage Center, the National Hangeul Museum, and the Korea Craft & Design Foundation. In addition, the exhibition features contemporary Canadian craftworks inspired by traditional Korean arts. These diverse subjects and identities envision a completely different dynamic of Korean beauty for the future, encouraging dialogues between different objects and concepts through communication, interconnection, and convergence. Posters designed by Minhye Park Titled as K-Lifestyle, the first exhibition in the series opens on Friday, February 23. Under the theme of Korean lifestyle, the exhibition introduces traditional Korean lifestyle practices and household items packaged by the National Folk Museum in Korea and donated to the KCC, called the Korean Culture Box. From the Box, K-Lifestyle displays the following: 1. <Sarangbang Box>: Showcasing the living space of Confucian scholars during the Joseon Dynasty in the 14th-19th century, emphasizing male spaces. 2. <Anbang Box>: Highlighting the hidden living space of women and their most cherished possessions during this restrictive Confucian society in the Joseon Dynasty. 3. <Annyeong Box>: Projecting sample images of Korean lifestyles from the past to the present while providing general information on Korea. Additionally, K-Lifestyle features Korean intangible cultural heritage objects created by nationally certified artisans from the National Intangible Heritage Center. <Sarangbang Box> <Anbang Box> The exhibition also features a model of the Moon Jar. This white porcelain was originally produced during the mid-Joseon Dynasty in the 17th and 18th centuries when Confucian scholars began searching for new social values through practical science, aiming to escape the weight of academy-heavy Chinese theories. Characterized as a Korean cultural icon worldwide, the Moon Jar embodies an unpretentious, gentle, and naturalistic approach inherent in Korean culture. It deeply served as artistic inspiration for the prolific Korean painter, the late Kim Hwan-ki. Notably, it was also sold for 6 billion Korean won at the Christie’s auction in New York in 2023. The cultural traditions and artistic expressions showcased in this exhibition have also inspired contemporary Korean craft artists. Alongside those traditional objects, the exhibition also includes contemporary craftworks by Korean-Canadian artists Chung-Im Kim and Joon-Hee Kim. Chung-Im Kim Chung-Im Kim has received accolades and exhibitions for her work in many prestigious institutions such as the Boston Museum of Art, the invitational Bojagi Exhibition at the Suwon Park Museum in Korea, the Museum Nagele in the Netherlands, the Wollongong Art Gallery in Australia, the Belgian Triennial Contemporary Textile Arts Exposition and the recent traveling exhibitions at the Poikilo Museum in Finland, Tamat Museum in Belgium, Dronninglund Kunstcenter in Denmark, and the Textilmuseum in Germany. Kim's design and execution have been honoured with prizes and awards in many international art competitions. She received her MFA from Seoul Women's University in 1984 and immigrated to Canada in 1990. Since then, Kim had worked as a freelance designer for many years and also taught at OCAD University in Toronto from 1997 until her retirement in 2021. She is represented by the Oeno Gallery. In her elegant monochromatic white tapestries, finely detailed patterns swirl around the fabric. Kim’s organic form is inspired by the patterns she sees in nature. The white ink on white fabric provides a subtle texture. By sewing small pieces of industrial felt together that are then pulled taut, Kim creates a web-like 3-D effect. The Korean-Canadian artist’s work is contemporary but it is also rooted in the rich traditions of her Korean homeland. Chung-Im Kim <Dawn>, 2009, 117*12*10.16cm Joon Hee Kim Joon Hee Kim’s work explores the significant perception of existing as a human being while examining and reconciling the diverse identities and heritage of the world, seeking out the compelling forces of beauty and desire. An award-winning ceramist who was an art director in her native South Korea, came to Canada and took patisserie studies at Le Cordon Bleu in Ottawa. However, switching careers, and graduating from Sheridan College, led her to become intrigued with ceramics. As the Cecil Lewis Sculpture Scholarship recipient, she completed a Master’s in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Arts in the UK. Her compelling ceramic works have been exhibited in the USA, Germany, UK, and they have also been in a solo exhibition at the Clay and Glass Gallery. She examines her heritage through the lenses of multiple influences as she travels to both national and international artist residencies. Following the Banff Clay Revival Residency, she was one of the six artists selected for the Canadian Craft Biennial. Then she attended the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park Residence in Japan, the Ceramic Centre Residency in Berlin, and most recently and prevalently the Archie Bray Foundation Residency. She was a recipient of a large variety of many honourable awards and grants, including the Helen Copeland Memorial Award for 6-consecutive years from the Craft Ontario Council, a considerable amount of grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and Ontario Arts Council, the Best of Student Exhibition from the Toronto Outdoor Fair later flourished in winning the Best of Ceramics, and Best of Craft and Design the ensuing year, as well as being awarded the prestigious Winifred Shantz National Award for an exceptional emerging ceramic artist. Her latest achievement derives from her work being chosen through numerous selections for the Royal Botanical Gardens' International Sculpture Collection in Burlington, Ontario, and great recognition was being selected as the Artist of the Year 2023 by the ITSLIQUID, a communication platform for contemporary art, architecture, design and fashion. Joon Hee Kim was also invited to a group exhibition, <Between Horizens: Korean Ceramic Artists in America> in the Clay Studio, Philadelphia in 2023. Joon Hee Kim < Something Divine>, 2023, 56*98*55cm During the exhibition, visitors can engage in various public events, including artist talks with contemporary craft workshops. If you’re interested, register for the following events: 1. K-Lifestyle: Opening Reception and Artist Talk by Ceramist Jun Hee Kim - Date: February 23, 2024 (Friday), 5:30 PM to 8:00 PM - Venue: Multipurpose Hall, Korea Cultural Centre - Registration: https://forms.gle/ewWYy1Xv5krfmott7 2. Artist Talk by Textile Artist Chung-Im Kim - Date: March 15, 2024 (Friday), 5:30 PM to 8:00 PM - Venue: Multipurpose Hall, Korea Cultural Center - Registration link will be provided later. 3. Traditional Hanok Experience: Create a 3D Hanok Puzzle Workshop - Date: March 22, 2024 (Friday), 5:30 PM to 8:00 PM - Venue: Multipurpose Hall, Korea Cultural Center - Registration link will be provided later. Korean Cultural Centre Canada Address: & Contact: - 150 Elgin Street, Unit 101, Ottawa, Ontario, K2P 1L4, Canada - Tel: 1-613-233-8008/ E-mail: canada@korea.kr Hours: Monday - Friday, 09:00 - 17:00 (Closed 12:00 - 13:00)

-

Two Special Exhibitions to Celebrate 2024 Seollal, the Year of the Blue Dragon

Post Date : Feb 08, 2024

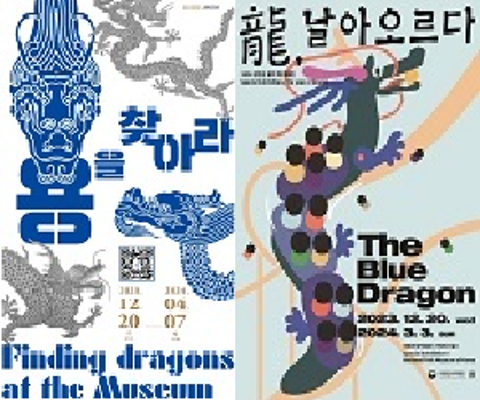

Event Date : Feb 08, 2024 - Feb 11, 2024On the upcoming 2024 Seollal on February 10, the Korean Cultural Centre Canada is pleased to introduce two very special exhibitions to our fellow Canadians, which celebrate the Year of the Blue Dragon in 2024. <The Blue Dragon> by the National Folk Museum of Korea (December 20, 2023 ~ March 3, 2024/ Special Exhibition Hall Ⅱ (NFMK Seoul)) <Finding Dragons at the Museum in Celebration of the Year of the Blue Dragon> by the National Museum of Korea (December 20, 2023 ~ April 7, 2024/ Permanent Gallery) Click the images below to find out about each exhibition. The Korean Cultural Centre Canada wishes everyone a Happy New Year! -

In Canadian Perspectives: Negotiating Borders

Post Date : Jan 26, 2024

Event Date : Jan 26, 2024 - Feb 15, 2024In Canadian Perspectives: Negotiating Borders In celebration of the closing of the <Negotiating Borders> exhibition in Ottawa on January 27, the Korean Cultural Centre shares three reviews and responses to the exhibition written by three Canadian writers. 1. Negotiating Borders (after Crash Landing on You), Paola Poletto (December, 2023) 2. DMZ, Paul Hong (December 2023), 3. Negotiating Borders: Korean Art, Maureen Korp (The OSCAR, December 2023) ----- 1. Negotiating Borders (after Crash Landing on You) Paola Poletto (December, 2023) This photograph conveys my feeling of being in FRAKTUR (Fracture) (2018) by Jeewi Lee, situated in a cubed room divided diagonally on the ground by white rocks and dark grey ones. To enter the room, located at the far end of SAW Gallery in Ottawa, one had to step onto the grey rocks first, roughly from the view you are looking into now. The crunchy - crunch beneath my feet echoed upward and beyond the room, amplifying my every move. It was as if I was under audio surveillance in an otherwise quiet gallery setting. In writing this to you now, I have the privilege of having left the room. I have re-compartmentalized the experience as a white cube thrice removed by space-time, of being hemispheres away from a politically divided country, and interpreting trauma through aestheticisms. On the north side of the room, top right of picture, there is a black-framed door, locked shut with a numbered lock pad: the glassed door looks into a hallway and across into the gallery’s administrative offices. In this photograph, the black-framed door is, metaphorically speaking, wonderfully ajar. It has made this photo response possible. I turn right to look at two framed takbon rubbings of trees in the DMZ, titled INZISION (Incision) (2018) not captured in this photo. They complement the floor work FRAKTUR (Fracture), both made by Lee. Their pairings echo what I experienced at the 2023 Gwangju Biennale, where multiple artworks made by the same artist show how their ideas germinate, carry and expand over time. Similarly, here, installations have grown tentacular arms with drawings and films meant to hug you and me, here, continents away from North and South Korea, with perhaps an offer to greater understanding of their political complexity. Lee’s individual art practice permeates. It renews with each new context and each new dialogue with an adjacent artwork, and another viewer. I look left to the blood-red wall work by the Nova Scotia-based HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, a stylistic cast impression of residential burglar bars that were salvaged from the window of a demolished post-war home in Seoul. The deep blue and red colour of this work overlord the room like a monster. Indeed, I feel trapped in this room. I move my cameraphone to a panoramic setting and begin to move through the space to take my photo. Each time I try to make my panorama, I get pulled into the centre of the room, sucked down into the rocks. My movements hasten. We are at 38-degree angles, body and machine, a simulation of the DMZ’s 38th parallel north: the photographs stop, start, stop, start; I stop, start, stop, start, together, frustratingly out of synch. I have chosen this photo here as the most representative photo of being complicit in the collective desire to negotiate borders, to moonwalk from ground with white rocks on the north side to the ground with grey rocks. In the other gallery, Ottawa-based Adrian Gollner offers an alternate mapping of the DMZ from Incheon to Cheorwon County with Trace (2023). A birdwatcher, he drew birds spotted on his journey walking publicly accessible parts of the DMZ. The drawings are pinned on the wall away from his blue vinyl line representing the GPS mapping of the zones he walked. The birds here, on this wall, most feet firmly planted, surround the no fly zone: they are, though, freely flying the DMZ. Across from this scene where every bird is named, is an encased child’s rubber boot, with drippings of paraffin wax over a blue sponge. Minouk Lim’s Farewell (2011) resonates across continents with sadness for every child lost to genocide. The sponge, sprawled out from the boot-like wings, wishes it into flight like a spirited bird. The boot accompanies a video work also by Lim called It’s a Name I Gave Myself (2018) that culls footage from a 138 day-long news broadcast made in 1983 that attempted to reunite lost family members scattered and fractured by the Korean War. Lim brings into view the horrifying footage of children separated from their families 30 years prior. As adults they don’t know their own birth names and some use memories of childhood scars and other physical attributes to reunite with family. I stand by the boot and look back toward this picture now. It is a reminder that my cameraphone and these words are also transmitted. Artificial Sun (2017) a single-channel video installation by Chan Sook Choi projects an image of a common heater lamp, rotating left to right to left, found throughout the homes of elderly women living in the Civilian Control Zone of the DMZ. Positioned up high on the wall, the projection could also be a cartoon retro space blaster, echoing the NOWness of the “rising tensions after launch of spy satellite in defiance of UN sanctions” (McCurry, 2023). Opposite this radiating sun are two seaweed-coloured lacquered flecks of fragmented South Korean newspapers pinned to the wall as part of HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander’s sprawled site-responsive installation, Leave Without Absence (2023). These and other materials are scattered by the artists throughout gallery spaces as various debris and imprints, such as the one I describe in the picture above in the room with FRAKTUR (Fracture). As “ideological scabs” (Kajander, 2023) which the artists describe as part of a larger project that “explores the associative implications of thresholds that attempt to keep things separate, limit passage, but may also catalyze transformation or act as points of departure,” these two flecks, for me, are two urgent things: the mapping of Palestine and Israel and other brutal active wars that are entangling the way I see this exhibition; and… they are also the left over flakes of gim on our plates after our family finishes off all the gimbap halmoni has dropped off for dinner. Notes: Justin McCurry, “North Korea moves heavy weapons to border with South,” November 27, 2023, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/27/north-korea-moves-heavy-weapons-to-border-with-south Kajander, Paul & HaeAnn Kwon, e-mail correspondence with author, December 18, 2023 About: I’ve traveled to South Korea 3 times, most recently to Suwon/Seoul, took a Train to Busan, and bus to Gwangju (2023). Travelling to and within this triangulation of places broadened my outsider understanding of regional cultural differences, politics and aesthetics beyond those I have gleaned from my partner Paul over 30 years, and more recently from popular Korean drama such as Crash Landing on You (2019/20), and comedic segments of Conan O’Brien and Steven Yeun travelling to the DMZ in 2016. The first time I travelled to Korea, Paul and I were recently married. He accompanied me first for work to Nagoya, Japan at the 2005 World Expo before staying with my in-laws in Suwon. The second time, my brother-in-law was married in a traditional Korean ceremony in the foothills of Seoul. Our daughters were lantern girls for Auntie Su and samcheon. My current practice-research works through the glitch panorama as a mapping site for embodied, multi-voiced experience. This is a methodology from which I can combine photography and words toward photopoetic response. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- DMZ The plan is straightforward and contingent on building a time machine. Then, we go back in time to 1983 to KBS headquarters in Seoul. KBS headquarters has 453 hours of tape from their original broadcast. They essentially did the initial audition process. It's a rice cooker rocking and bubbling with pent up unreleased emotions. On tape number 112, you'll find the story of a man, a minam, named Kangjeon Kwang- Mo. He was 36 years old in 1983. When he was four, his mother left him with his neighbour while she went to find their father in Incheon. What was supposed to take five days turned into forever because of the Chinese New Years Offensive (and the fact that the father had another family in Incheon and that they had already fled to Busan). The neighbour fled Seoul with the boy but lost track of him in Suwon when he was off- loaded on to someone else's horse-drawn wagon. He was later found wandering in the streets by retreating American forces and deposited at an orphanage. During the 1983 KBS operation to reunite families, Kwang-Mo, who was a part-time gigolo and a performer in a traditional Korean dance troupe, thought he had found his long-lost mother but it turned out to be a case of mistaken identity. Hence, Kwang-Mo, like the song, was alone again (naturally). Outwardly serene, he is supersaturated with bitterness, disappointment, resentment, anger, sadness, loneliness, despair, betrayal, and a deep mistrust of the universe. Through proper handling and management, we ensure an alchemical sublimation of his turbulent soul and undoubtedly produce a shining star unlike any other. Kangjeon Kwang-Mo will be our first recruit-trainee and the leader, the visual, and lead dancer of a super K-pop band of the 21st century. The time is ripe for a new type of band. Not a band made of lost, hungry always- dieting, dye-damaged hair kids-as-commodities but adults starved by circumstances and hardship and hair greying with age. A group, an image, a brand, an ethos built on a foundation of years of suffering, hardship, want, absence, melancholy, despair, terror, and helplessness. Their music and dancing and very presence will bring about the catharsis -- a sublime catharsis unknown these days -- so badly needed, and finally exorcise the ghosts of Japanese annexation and foreign rule, civil war, and separation. They will be the necessary counterweight to the ungrounded illusion of endless growth, rampant unfettered consumption, and insatiable greed. The future needs the past desperately. But we found out that Kwang-Mo was still alive apparently and lived in a town near the DMZ. His dancing and gigolo days far behind him, he sometimes plows a field and hangs up home-brewed scarecrows. We went to search for him. What we didn't expect was that the DMZ, even the outlying areas approaching the actual zone, are beset with ghosts. They were everywhere. They were stuck in a liminal zone. An eternal departure lounge in an airport that neither sends off nor welcomes any flights. A train station in the middle of nowhere waiting for a train that will never come or doesn't even exist. Unable to leave the zone due to some sort of other world landmines and barbwire and ever-watchful sentry towers. They wander and are greedy for company with the living. The DMZ is the space between dreams and reality. And that's where we found my uncle -- or at least that's who the red-crowned crane claimed to be. The only boy and youngest in a family of 7 girls and hence the jewel of the family. Just a baby, he was taken by his father and a servant on a train heading to Busan during the New Years retreat. The mother and the sisters along with their housemaid were put on a horse drawn carriage and given an address to meet up in Busan. But somewhere near Jirisan, while waiting for another train, the story goes, a tiger emerged from the forest and grabbed him while his father was asleep. Another story claims a family who lost all their children kidnapped him. Another claims a giant eagle plucked him out of a makeshift cradle in broad daylight. "How do you know me?" I asked, while filming the red-crowned crane standing on the other side of the electrified fence in the DMZ. "I wasn't even born when you disappeared." The crane then went on to narrate the major events and locations of my life up to the point where I left Korea and the names of his sisters. "Why are you a crane?" "How else am I to talk to you? At any rate, I'm glad you came to visit." "What happened to you during the war?" "A man and woman who lost their children, kidnapped me and ran off into the forest. Shortly afterwards, a mother black bear who harboured deep resentment towards people since her cubs had been taken away, killed the man and woman and adopted me but I died a few years later due to malnutrition." A few other cranes landed on a nearby tree. "Why are you here, anyway?" my uncle who was speaking through or as a red- crowned crane asked. I told him my plan to build a new super k-pop group. I told him some of the names for the band we came up with: • Demigods of the Modern Zone • Denizens of the Mighty Zone • Denizens of the Machinations of a new age Zone • Demiurges of the new Magnificent Zone • Dynamos of the Modern Zone "What's K-pop?" he asked. I tried to explain. "Why don't you fly over to this side?" He refused. I had a brilliant idea. "Let's face-time my mom! Wouldn't you like to see your sister? It's been so long." She picked up, finally. I told her we had located her long-lost brother whom she barely remembered. She looked at me blankly. There is the wailing deep from the haunted caverns of the soul accompanied by fists beating against the chest. There is gnashing of teeth louder than the propaganda radio transmissions blaring on speakers pointed both north and south along the DMZ. Instead the two stared at each other wordlessly through the phone. "You haven’t called out your sister's name, yet," I said to my uncle, the crane. "Why don’t you call out for her? Let it out. For all of us. We're filming this." The crane, my uncle, looked at me. "Don't be afraid. Let it out. The years of torment and hardship locked within you. Unlock it. Release it! Wail your soul out!" A pitiful shrill shriek arose from its long neck and emerged from its beak and then dissipated into a wisp in the cold air. "Okay, " I turned to my mother. "Is there something you want to say to your beloved long-lost baby brother?" "That's a bird," she stated. My uncle, an endangered species of crane, stared at my phone and tilted his head to one side and then to another. He then said: "You’ve grown so old. I can hardly recognize you, now. How did you grow so old?" Author Bio: Paul Hong is a writer and librarian who was born in South Korea and has lived in Canada for most of his life. He is co-authoring a book about one of the first Koreans to visit Canada, or more specifically, one particular family farm in Southwestern Ontario in the early 20th century. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3. Negotiating Borders: Korean Art, Maureen Korp (The OSCAR, December 2023) --https://oldottawasouth.ca/oscar-archives/2023/12/01/2023-12-december/ (Check out the Page 32)

About KCC

KOREAN CULTURAL CENTER